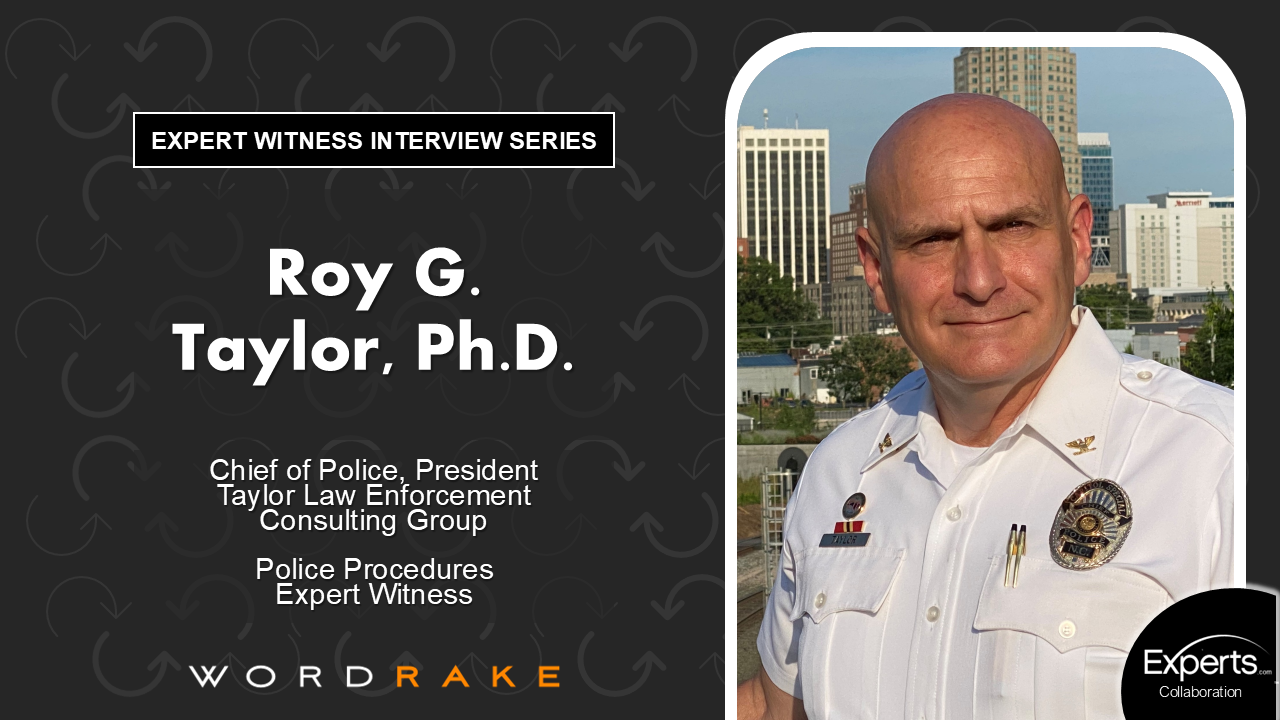

Roy G. Taylor, Ph.D., a current Chief of Police, has over 40 years of experience in Police Practices and Procedures and Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice. Through Taylor Law Enforcement Consultant Group, he provides consultation and expert witness services to attorneys, municipalities, the insurance industry, and other clients. Read Dr. Taylor's insight into his expert witness practice and array of law enforcement positions.

What is your professional background, and how did you become an expert witness?

I became an expert witness through a blend of long service, formal education, and recognizing gaps in how policing impacts communities. Too often, I see experts assume that years in uniform automatically translate into credibility in the courtroom. That shortcut risks overlooking the need to connect professional experience to accepted legal standards and clear, unbiased analysis.

My background includes 45 years in law enforcement, 31 of which were spent as a Chief of Police, and 24 years in the U.S. Army Reserve, where I served as a Military Police Lieutenant Colonel and Provost Marshal. I also hold a Ph.D. in Criminal Justice. But those credentials alone are not enough. When I founded Taylor Law Enforcement Consulting Group 11 years ago, I made a conscious decision to study the systemic issues, especially the troubling number of civil rights violations and fatal encounters with people in mental health crisis.

As an expert witness, I handle things differently: I don’t rely on assumptions or broad generalizations. Instead, I apply nationally recognized standards, policies, and training expectations to each fact pattern. I explain not only what should have been done, but why—so jurors, attorneys, and courts can understand the reasoning. This disciplined approach avoids advocacy and builds credibility, while also teaching others about safer and more constitutional policing practices.

What kinds of cases do you typically work on, and what types of attorneys or law firms seek your expertise?

Most of my work involves §1983 Civil Rights lawsuits, where the central issue is whether law enforcement actions violated constitutional protections. A common assumption is that experts only testify for police agencies or only for plaintiffs. The risk in that shortcut is overlooking the importance of balance—credibility comes from applying standards consistently, not favoring one side.

In practice, about 20 percent of my cases are for the defense, usually representing a law enforcement agency. The other 80 percent are for plaintiffs, where I am asked to evaluate whether an individual’s rights were violated, most often under the Fourth Amendment. These cases frequently involve the use of force, police pursuits, searches, and encounters with people experiencing mental health crises.

The attorneys and law firms that retain me are generally those with strong federal civil rights practices. They look for someone who not only has extensive law enforcement experience but who can also explain to judges and jurors how nationally recognized standards apply to real-world police encounters. My role is to bridge that gap—making complex policies and procedures understandable while showing where they align, or fail to align, with constitutional requirements.

How do you prepare to write an expert witness report?

When preparing to write an expert witness report, I approach the task in the same way I train officers: with detail, discipline, and documentation. Too often, I see experts fall into the shortcut of relying on rank and experience to carry the day. The risk in that approach is twofold—it may appear biased, and it leaves gaps that opposing counsel will quickly exploit.

My process begins with a thorough review of the case file, which includes reports, depositions, policies, body-worn camera footage, and relevant statutes. I identify the facts I can independently verify and separate them from assumptions or opinions. Next, I map those facts against nationally recognized standards, training protocols, and case law. This ensures that my opinions rest on accepted benchmarks, not just personal experience.

From there, I draft the report in clear, numbered sections—introduction, methodology, findings, and opinions—always documenting where each conclusion is drawn. I write with the jury in mind, using plain language so complex police procedures are accessible to laypersons. This approach not only strengthens credibility but also demonstrates my role as an educator. The goal is not advocacy, but clarity: demonstrating how professional standards are applied, where they are met, and where they are not.

How do you avoid overwhelming non-expert readers with technical language?

This is one of the most important skills for an expert witness—because if your audience can’t follow your reasoning, your expertise won’t carry weight. The common shortcut I’ve seen is experts leaning on jargon or acronyms, assuming everyone in the room “already knows.” The risk is that jurors and even judges may tune out, misunderstand, or think the expert is trying to obscure weaknesses.

I approach it differently. First, I translate technical terms into plain English before I use them. For example, instead of writing “ECW,” I’ll write “electronic control weapon (commonly known as a Taser)” the first time, and then use the plain term throughout. Second, I rely on analogies from everyday life. If I’m explaining reaction time in use-of-force cases, I might compare it to how long it takes a driver to hit the brakes when a deer runs across the road.

Finally, I structure my reports so each section begins with the “bottom line” in plain language, followed by the technical explanation for those who want depth. That way, non-expert readers grasp the core opinion quickly, and attorneys can choose how much technical material to emphasize in court. This balance builds credibility by showing mastery without alienating the audience.

How does online visibility—like directories or profiles—help attorneys find you and evaluate your practice?

Online visibility is no longer optional—it is the way attorneys research, vet, and ultimately decide whether to reach out to an expert. A common assumption I see is that “my CV speaks for itself,” and therefore posting it somewhere online is enough. The risk with that shortcut is that a static résumé doesn’t communicate accessibility, professionalism, or how your expertise translates into usable courtroom testimony.

Directories and professional profiles fill that gap. They allow attorneys to quickly see not just my qualifications, but also my areas of specialty, publications, and case experience. More importantly, they demonstrate that I am active, engaged, and responsive in my field—qualities lawyers look for when deadlines are tight and credibility is on the line.

I continue my membership with Experts.com because it enhances my professional visibility in a trusted environment. Unlike broad social media, Experts.com is a curated space where attorneys know they can find seasoned experts. It also signals my commitment to maintaining high professional standards and being available to contribute in complex cases. In short, it is both a teaching tool—showing how I think and write—and a credibility marker that helps attorneys evaluate whether I am the right fit for their case.

Have you ever had to revise a report after feedback that wasn't clear or persuasive enough? What did you learn?

Yes, I have revised reports after receiving feedback that certain sections weren’t as clear or persuasive as they needed to be. Some experts assume that once they’ve written their opinions, their job is finished. The risk with that shortcut is overlooking the fact that reports don’t exist in isolation—they must integrate into an attorney’s overall trial strategy and resonate with a non-expert audience, especially jurors.

When this has happened, I’ve worked closely with my client attorneys to clarify what points needed sharpening. I learned the importance of presenting my opinions and organizing them in a way that flows logically and is easy to follow. I also became more deliberate about tying every opinion to a supporting document, policy, or recognized standard. That discipline both strengthens the credibility of my conclusions and reassures counsel that the opinions can withstand scrutiny.

Ultimately, revisions taught me that clarity isn’t just about simplifying language. It’s about structuring information so that attorneys, judges, and jurors can see the direct path from evidence to conclusion. This collaborative process makes the report a stronger tool for trial.

What do you wish lawyers knew about working with expert witnesses?

A common assumption lawyers make is that once they retain an expert, the expert will “just know what to do.” The risk in that shortcut is misalignment—an expert may focus on issues that don’t support the trial theory or miss opportunities to connect technical analysis with the themes the jury needs to hear.

What I wish lawyers knew is that the strongest expert work comes from collaboration. I don’t need coaching on my opinions, but I do benefit from clarity on what aspects of the case they believe will be most persuasive. Early and open communication allows me to tailor my analysis, organization, and explanations in a way that directly supports their strategy while still maintaining independence.

I also wish attorneys realized that providing complete materials—policies, training records, body-worn camera footage, deposition transcripts—makes a tremendous difference. Gaps in discovery often translate into weaker opinions. My role is to explain professional standards clearly and fairly, and I can do that best when I have all the context.

Working with an expert isn’t just about having someone with credentials on the stand. It’s about integrating specialized knowledge into the larger story of the case so the jury can understand not only what happened, but why it mattered.

As an expert witness, do you think there is a disconnect between the expert witness communities and attorneys and law firms?

Yes, I do see a disconnect. Many attorneys assume that experts will automatically understand the nuances of trial preparation and courtroom strategy. The risk in that shortcut is frustration on both sides, lawyers may feel the expert is not providing what they need, while experts may feel underutilized or unclear on expectations.

The legal industry can bridge this gap by fostering more intentional communication and training. For example, early case conferences that include both counsel and the expert allow for alignment on scope, key issues, and deliverables. Attorneys should be clear about timelines, preferred report structure, and the strategic emphasis they want, while still respecting the expert’s independence.

I also believe law firms would benefit from learning more about the role of an expert witness beyond testimony—such as helping identify overlooked discovery, highlighting policy gaps, or clarifying industry standards. On the expert side, we must be proactive in asking clarifying questions and explaining how we work.

Ultimately, bridging the disconnect is about partnership. When attorneys and experts treat each other as part of the same team with different but complementary roles, the result is a more coherent case presentation and stronger advocacy for the client.

What do you think most experts underestimate about being "discoverable" to attorneys?

Most experts underestimate that being “discoverable” isn’t just about being listed somewhere—it’s about being visible in the right places, with the right information. A common assumption is that posting a résumé on a personal website or LinkedIn profile is enough. The risk in that shortcut is twofold: attorneys may never see it, and even if they do, they may not find the specific expertise or litigation experience they are searching for.

Attorneys are busy. They want to quickly confirm qualifications, areas of specialization, and whether an expert has courtroom credibility. If that information is buried or incomplete, they may move on to someone else. Discoverability is really about making your experience accessible, verifiable, and easy to evaluate.

Experts.com addresses these concerns by providing a dedicated and trusted platform specifically designed for the legal industry. Unlike broad professional sites, it organizes information in a way that attorneys search by subject matter expertise, jurisdiction, and case type. It also signals professionalism: being on a vetted directory shows that you take expert work seriously. For me, Experts.com ensures that my decades of experience in law enforcement, the military, and academia are presented clearly and concisely, making it easier for attorneys to find me and determine whether I’m the right fit for their case.

About the Author

Dr. Roy G. Taylor is a seasoned law enforcement executive with more than 45 years of experience across federal, state, local, and private criminal justice positions. He is a nationally recognized consultant, expert witness, and speaker on police reform, crisis intervention, leadership, civil rights, community policing, and law enforcement training. His expertise is frequently sought by attorneys, policymakers, and professional associations, and his insights are regularly featured in both local and national media outlets.

Throughout his career, Dr. Taylor has contributed to the advancement of policing through keynote addresses, guest lectures, training programs, and consulting services. His areas of expertise include community program development, officer recruiting and selection, employee supervision and evaluation, budgeting, curriculum development, policy and procedure design, and public relations. He is also a best-selling author; his most recent book, Being a One Percenter, explores leadership and resilience in the law enforcement profession.

An active member of the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP), Dr. Taylor serves on the Civil Rights Committee and participates in the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) as well as the Occoneechee Council’s Scouting Explorers program. His career has been distinguished by numerous honors, including the prestigious North Carolina Order of the Long Leaf Pine, the National League of Cities Community Policing Award, the IACP Traffic Safety Award, the Veterans of Foreign Wars North Carolina Police Officer of the Year, and the North Carolina Governor’s Crime Prevention Award.

In addition to his civilian leadership, Lieutenant Colonel Taylor served 24 years in the U.S. Army National Guard and U.S. Army Reserve as a Military Police Commander. He retired in 2022 after holding several key assignments, earning the Bronze Star with Valor for his service in Iraq, as well as the Defense Meritorious Service Medal, the Joint Achievement Medal, and multiple commendations for leadership and operational excellence.

Today, Dr. Taylor brings his extensive experience and deep commitment to civil rights and community-focused policing into his consulting and litigation support practice. He specializes in federal §1983 civil rights cases, where his expertise helps courts, attorneys, and juries understand accepted police practices, training standards, and constitutional requirements. Through this work, he continues to shape the future of law enforcement and public safety.

Visit Dr. Taylor's Experts.com profile and connect with him on LinkedIn.