Who must comply with plain language laws? Nearly everyone in business. According to Professor Michael Blasie, the leading expert on plain language laws, in addition to the federal government’s plain language laws, every state in the United States and Washington DC have plain language laws too. In an earlier article, we discussed federal plain language requirements; this article focuses on state laws that determine how private actors must write.

Sources of Plain Language Laws

In Blasie’s new book United States Plain Language Laws: The Laws Revolutionizing Transactional and Governmental Document Design, published by Wolters Kluwer Legal & Regulatory U.S., he delivers a history of the plain language movement and the only known centralized list of U.S. plain language laws.

In a pithy summary of his book on the Plain Language International (PLAIN) group on LinkedIn, he wrote:

Of the 768 U.S. plain language laws, 577 cover documents drafted by the private sector: contracts, waivers, securities filings, and more. Consumer protection documents (non-negotiable template mass-use documents produced by businesses and given to consumers) are over 75%. Other concentrations are in housing, property, and healthcare too. The coverage shows which industries lawmakers think need improvement.

Since this post, 230 more plain language law have been passed in the US, bringing the total to 998. Professor Blasie spoke in more detail about them in this plain language law primer.

History of the Plain Language Movement

The plain language movement in the U.S. started in the early 1940s when Congress passed the Federal Reports Act. At that time, the goal was to reduce complexity and duplication of information. By the 1980s, focus had shifted to reducing language difficulty, as seen in the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1980. By the early 2000s, the focus had shifted again to the broader goal of reader understanding. Karen A. Schriver, PhD, details the goals and history of the movement in Plain Language in the US Gains Momentum: 1940–2015.

In her research paper, Schriver explains how we came to the current definition of plain language:

Between 2008 and 2014, three prominent plain language groups (the Center for Plain Language, Clarity International, and Plain Language Association International) collaborated to specify Redish’s definition further: A communication is in plain language if its wording, structure, and design are so clear that the intended audience can easily find what they need, understand what they find, and use that information.

When to Use Plain Language

When a writer has far more knowledge or information than their audience, the writer should choose plain language. If the writer ignores the information asymmetry and writes as though they’re writing to a colleague with equal information, emotional capacity, and time to understand, then the message dies before it’s delivered.

In Finding Empathy for Users: A Plain Language Model, Professor Russell Willerton offered a framework for recognizing when a writer should use plain language and empathy.

- Bureaucratic. If your reader must deal with a large, faceless organization; learn new policies and procedures; or search for complex information, they’re in a bureaucratic situation. It’s your job to communicate clearly and empathetically so your reader can understand this complex information and act quickly.

- Unfamiliar. If your reader is in a new situation, they’ll need all the help they can get to navigate it. For example, they may be confronted with paperwork in a language not familiar to them—a foreign language, terms of art, legalese, or business jargon. You must simplify information when explaining new ideas to them.

- Rights-oriented. If your reader’s rights are at risk, they could face serious repercussions. You must show them where to start and help them understand what’s at risk. It’s vital that you guide your reader and explain why they can’t wait to act.

- Critical. If your reader’s life or livelihood is at imminent risk, then the situation is critical, and misunderstandings can lead to dire consequences. Unexpected situations may arise, which could cloud your reader’s judgment and performance. Be patient and emphasize the importance of any time-sensitive tasks.

Common areas where the writer has more information, but does not bear the same consequences of misunderstanding the information, include healthcare, consumer finance, food and product safety, social services, immigration, housing, privacy, employment, and fraud.

How WordRake Helps Achieve Plain Language Goals

WordRake helps writers meet plain language goals by reducing sentence length and swapping difficult words for simple ones. In Brevity mode, WordRake cuts needless words and modifiers and shortens sentences. In Simplicity mode, WordRake helps writers choose simpler words. Between both modes, WordRake offers edits for about 90% of the 237 suggested simplifications on PlainLanguage.gov. (This list is described as “a specific list of everyday words that you should substitute for legalistic or bureaucratic terms”). If you use both Brevity and Simplicity editing modes, you will receive about 2/3 of editing suggestions from Brevity mode and 1/3 from Simplicity mode because WordRake prioritizes Brevity suggestions. To maximize plain language-focused suggestions, run Simplicity mode first, then accept or reject suggestions, then run Brevity mode.

How WordRake Helps Improve Readability Metrics

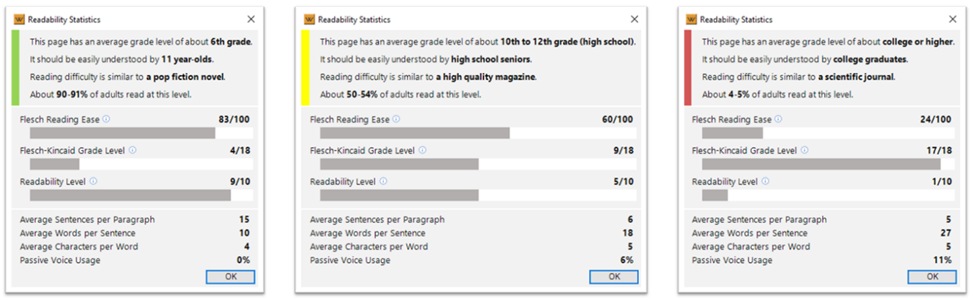

WordRake also offers readability metrics to help writers see the consequences of their writing choices and improve readability before sending a document. This readability feature builds on Microsoft’s offering and makes it easy to view your document’s scores for reading ease, grade level, and readability.

- The Flesch Reading Ease score evaluates average sentence length and number of syllables per word. It uses a 100-point scale: the higher the score, the easier it is to understand the document.

- The Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level score rates text based on U.S. grade-level reading standards. A score of 8.0 means that an eighth grader can understand the document. For most documents, aim for a score of about 7.0 to 8.0.

To get this information, click the Check Complexity button on the WordRake ribbon. Unlike Microsoft’s built-in feature, you need not run spellcheck before getting your scores.

A Quick Way to Improve Clarity, Brevity, and Simplicity

The clearest documents come from editing, organizing, and user testing, but the pace and constraints of business don’t always allow for it. To improve your document quickly with the resources available, try WordRake. For $229 per year, you’ll have access to two editing modes: Simplicity mode, which prioritizes familiar words and helps meet plain language guidelines; and Brevity mode, which prioritizes succinct writing and offers suggestions to make writing concise and compelling. Using both modes, WordRake offers over 50,000 editing algorithms appropriate for any type of writing in any regional spelling style. View a list of hundreds of editing examples here. Try WordRake free for seven days now!

About the Author

Ivy B. Grey is the Chief Strategy & Growth Officer for WordRake. Before joining the team, she practiced bankruptcy law for ten years. She represented banks, debtors, and a chapter 7 trustee, so she has experience complying with plain language laws designed to protect consumers, such as the Truth in Lending Act, the Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act, and the Consumer Leasing Act. Ivy was also the Director of the Executive Secretariat for the Department of Commerce during the 2021 transition. This office is responsible for enforcing the Plain Writing Act for the department. Ivy has been recognized as an Influential Woman in Legal Tech by ILTA, a Fastcase 50 Honoree, and Women of Legal Tech honoree by the ABA Legal Technology Resource Center. Follow Ivy on Twitter @IvyBGrey or connect with her on LinkedIn.